home > archive > the history of 6m > 50 years of 50 MHz part 4

Thanks to all of our authors since 1982!

50 Years of 50 MHz Part 4 - Ken Willis, G8VR |

|

|

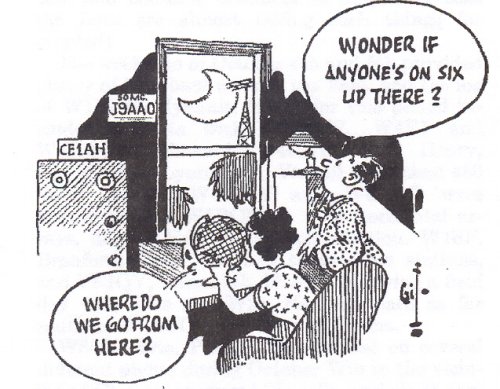

It was my good friend Bob Reif, W1XP who was quickly on the e-mail to remind me that the UK was not the only place where pre-war 56MHz operation was to be found. Other countries had the band, notably the USA where as early as the 1920s ‘Five Metres’ was a popular and much-used band. The steady progress made on this band in America is evidenced by a contact made on July 22nd 1938 between W1EYM and W6DNS over a path-length of 2500 miles, a new record and far in excess of anything achieved on the band in the UK prior to 1939. But this was Five Metres, so what’s the relevance to the Magic Band? How the ‘Magic Band’ was born It came about in this way. In 1944 some decisions were taken by the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) which, had the outcome been different, could have resulted in there never being a 50MHz amateur band at all and consequently none of those six-metre DXCCs nor any of the spine-tingling rare-prefix contacts which have been features of this and the previous solar cycle. With World War II not yet over, the FCC embarked on a programme of post-war frequency allocations, the 44-108 MHz part of the spectrum being of particular interest. This slot was earmarked for both television and FM broadcast services, where a huge post-war increase in the number of stations was anticipated. There was a single amateur band within this range (56-60MHz) and with so many demands on the spectrum it would have been all too easy for the FCC to have selected an amateur allocation and presented it as a fait accompli but it did not. Instead the American Radio Relay League (ARRL), representing the American amateur radio movement, was invited to participate in the decision-making process. I believe that this was a further indication of the goodwill that always existed between the FCC and American radio amateurs, though on this occasion FCC may have had a motive in bringing ARRL into their discussions. The FCC presented the ARRL with three alternative band-plans for study, following which delegates from both sides would attend hearings where the issues would be debated and finalised. In allocating frequencies for FM broadcast stations, FCC was concerned that sporadic-E propagation spanning the continent during summer months might cause havoc through co-channel interference if the wrong band was chosen for the service. It was in this area that some input from the ARRL could be useful, since radio amateurs had enjoyed and exploited this mode of propagation on their 56 MHz band for years. With little or no commercial interest in this part of the spectrum at that time, amateurs probably knew a lot more about sporadic-E than many of the FCC engineers. In the first of the three alternative plans submitted to the ARRL, the FM broadcast service was placed in the 54 - 68 MHz band, right on top of the existing five-metre allocation. Amateurs would then move down to 44-48 MHz. The second would allow amateurs to retain their existing 56-60 MHz band with FM broadcast assigned to 72-86 MHz. The final proposal offered amateurs 50-54 MHz with FM broadcast on 88-102 MHz. One can imagine how eyes must have lit up at ARRL at the prospect of an amateur band starting at 50MHz. First, however, the League had to present its case and convince FCC that alternative three met a majority of both commercial and amateur requirements. The ARRL’s general manager, Kenneth B Warner, was nominated as its main delegate. Space only allows me only to paraphrase his presentation at the final hearing, but suffice it to say that while it was wholly professional, he could resort to very informal ‘ham radio’ language in arguing his case. He opened by saying: “You propose to shift our band of 56-60 MHz, the first ever allocated in that part of the spectrum, to 50-54 MHz. We said that while we embrace that, it must be regarded as the limit of acceptable displacement.” (That’s telling ‘em!). He continued: “FCC Alternative No. 1 is distasteful to us because it would move the amateur band down to 44-48 MHz, and if move we must, we would much prefer not to move below 50MHz. We have done much work in the vicinity of 56MHz observing and studying the behaviour of these waves and we regard that job as incomplete and consider 50MHz to be the lowest frequency to which we could move and permit continuity.” Warner then showed he knew all about six metres when he said: “Frequencies in the vicinity of 56-60 MHz have a particular interest for amateurs because they are located at what seems to be a unique transition spot in the spectrum. Sporadic-E occurs just sufficiently often to maintain amateur interest at white heat, and such frequencies are near the top-limit of where F2 transmission ever normally occurs “ Referring to information ARRL had provided earlier, and using slightly emotive language to describe the 56MHz band, he continued: “We have previously characterised the performance of this band to you as being erratic, unpredictable, unreliable and unexpected, a band where anything can and generally does happen, and we have explained that its very eccentricities give it a peculiar charm for us , though they make it singularly bad for regular service. If we were moved to 41-48 MHz, it would be in a region where both sporadic E and F2 transmission occur so frequently that they would possess small novelty and much of the eager interest of amateur observers would disappear. The band would be neither fish nor fowl but regarded simply as an exceedingly unreliable long-distance band.” Now came the point where the ARRL hoped to steer the committee towards alternative three and give amateurs the coveted 50-54 MHz allocation. Since he was addressing a group with engineering backgrounds, he could employ a technical argument and he made a few assumptions. He anticipated that after the war there would be large numbers of radio amateurs living in any typical community. Should either 50-68 MHz or 72-86 MHz bands be given over to FM broadcast, receivers for both of these bands would require an IF in the 10MHz region, with local oscillators probably running on the low frequency side. This would make these receivers very susceptible to interference from amateurs who would then be operating in either the 44 MHz or 56 MHz bands. Next, to strengthen the case for putting FM in the highest range of 88-102 MHz, he brought up the subject of sporadic-E, commenting that: “Any person, amateur or not, who has heard sporadic-E bring in signals of local strength from a thousand miles away on the humblest receiver knows that considerations of sporadic-E alone compel the location of the FM service at a sufficiently high frequency to prevent this phenomenon from reaching it.” So here was a powerful American agency, with a large staff of professional engineers, being nudged by a radio amateur towards a decision that would have repercussions throughout US radio and television industry! The ARRL went on record as being opposed to alternative one but accepting alternative three. The FCC carried out some sporadic-E tests, which must have satisfied them as to Warner’s predictions because on June 27th 1945 it was announced that alternative three was to be adopted. The rest is history. US amateurs got 50-54 MHz and the ‘Magic Band’ was born. We in the UK and much of Europe had to wait forty more years or so for its general release. Okinawa Less than two months later, the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought to an end the war with Japan, Germany having already surrendered. This left thousands of American military personnel in occupation of Japan and some neighbouring Pacific islands and for many of them it would be a long stay before they got back home. Among them was a sizeable contingent of radio amateurs, who found themselves surrounded by masses of largely superfluous military radio equipment. It has always been a feature of US amateur licences that they permit the handling of third-party traffic, so the GI hams were quick to see that amateur radio would be the perfect way to keep in touch with home. The military saw its advantages too, and took swift action. An order was promulgated to the effect that Headquarters Eighth Army would assign calls to allied troops who already held operator licences. Initially it was ruled that operators would use their home calls signing the portable indicator ‘J’, but this changed when Japan was sub-divided into 9 call areas, similar to the USA system, and three-letter J-calls such as J4AAA started popping up on the HF bands. Many old-timers will recall hearing and working some of the J+3 prefixes from the Pacific on the 14 and 28 MHz bands during 1946-7. It was inevitable that some of the pre-war 56 MHz addicts now on a Pacific island would want to sample the new six-metre band just as soon as they could find a military radio which could be persuaded to operate on it. They were fortunate in that solar cycle 18 was near its peak, and it was a good one. Okinawa Island, lying between the East China Sea and the Pacific to the south of Japan, was one of the occupied territories and was assigned the prefix J9. The several amateurs stationed there formed themselves into a very active group and became well known as the J9’ers Radio Club. Several of them, including J9AAK and J9AAO, were six metre enthusiasts. Early in 1947, on January 25th, J9AAK had a notable contact with KH6DD in Oahu, Hawaii, over a distance of 4600 miles; this broke all records. They made two contacts during the afternoon with signals briefly peaking at over S9. Reports for the period state that J9AAK was using 68 watts (strange figure!) to a five-element close-spaced array, while KH6DD fed 500 watts into a “Twin-Three” array - an antenna system unknown to me. These contacts raised six metre activity among the W6’s on the American West Coast to fever pitch, with daily schedules maintained with Okinawa, while strategically placed on Wake Island in mid-Pacific was W6VDG/KW6, a useful ‘half-way house’. But the next big surprise which the magic band had in store did not involve the continental USA at all. Chile Our scene now shifts to the small copper-mining town of Chuquicamata (try spelling that out phonetically in a pile-up!) in the Andes mountains of Chile, the home of Larry, CE1AH and his wife Ida, CE1AJ, both six metre enthusiasts. In their remote location even the most basic components and materials to build a rig and antenna are non-existent, everything having to be shipped in over the mountains from afar (“Ida, they forgot the solder again!”). When the rig is finally built, day after day spent in careful listening results in nothing being heard on the band. Maybe the receiver doesn’t work or the antenna is dud, who knows? No test gear within hundreds of miles, no other station to carry out a check. Then at last, as more six-metre stations become operational, sporadic-E finally climbs the 18,000-foot mountains to reach Chuquicamata and some contacts are made with LU and PY. Meanwhile Larry is working the DX on some of the HF bands, and one day on 28 MHz he hooks up with J9AAO on Okinawa - not a bad ten-metre contact in its own right. By now J9AAO’s achievements on Six are legendary, so Larry begs for a try on 50MHz, knowing full well that a contact will be impossible of course since the J9 is situated half the world away. Conditions don’t seem all that hot in Okinawa either, and the GI at that end is about to leave the house for a date anyway so he’s not very interested. But he’ll settle for leaving his automatic keyer running while he is out, just to keep CE1AH happy. Half-way down the pathway to his Jeep, all sorts of pandemonium bursts forth from the vehicle’s on-board mobile ten-metre monitoring receiver - frantic calls from Larry saying he is hearing J9AAO’s 50MHz beacon. The GI runs back, and with hands a-tremble, switches on the main rig, picks up the mic and puts out a call, knowing for sure that like a thousand others there will be no response. But this time back comes the hoarse voice of Larry who is now copying J9AAO, on voice at S3! They make a two-way contact lasting just seven minutes before signals fade - a new world record, and what a payback for all those months of effort by CE1AH. The date was October 17th 1947, the distance now recognised as 10,500 miles and believed at the time to be virtually unbeatable because the stations were located almost exactly diametrically opposite one another on the planet (see the cartoon which appeared in QST for December 1947). This was long before we had GPS, computer programs, grids and all that good stuff to calculate distances. In reporting the contact in his Short Wave Magazine column, G2XC tried resorting to trigonometry and came up with 11,300 miles.

Final What is the world distance record on Six anyway? I once held a record, for about ten minutes, and I have a certificate to prove it. On 15th February 1992 I worked VK4KK on six metres, over a distance (so the parchment says) of 16416 kilometres or 10202.6 miles, a distance-record for any VK4 station for the band. Note that 0.6-mile. And hey! that’s only 297.4 miles short of the J9AAO-CE1AH contact . With the certificate came a nice letter from the Wireless Institute of Australia saying “unfortunately, following your contact with VK4KK, he worked another station about 75 miles to your west, so the record passed to him.” What I want to know is how did they know it was short path and not long path? Don’t you just hate those “unfortunately” letters?

UKSMG Six News issue 73, May 2002 |

the early history of 6m

six in fifty-seven

down memory lane

6m history

historical 6m

rigs

6m history by G6DH

50yrs of 50megs

pt1

50yrs of 50megs pt2

50yrs of 50megs pt3